Turnabout is fair play. Having analysed several thousand poems from Poetry magazine, I have decided to turn the same methodology on myself.

I analysed 5,751 words from the 79 poems from my current pamphlet The Silence Teacher and my forthcoming collection The Knowledge.

Here are my top twenty-five most commonly-used words:

- air (27)

- light (26)

- eyes (23)

- day (21)

- water (20)

- night (20)

- face (19)

- man (17)

- hands (17)

- hand (16)

- life (15)

- place (15)

- head (14)

- small (14)

- world (14)

- sound (13)

- hold (12)

- fingers (12)

- love (12)

- long (12)

- late (12)

- white (12)

- blue (12)

- dark (11)

- call (11)

Ouch. Far from the nuanced poet I aspire to be, this reads like I missed my calling writing second-rate Raymond Chandler pastiche, romance novels, or a truly bizarre hybrid of the two. But again, the frequently-used words are actually used relatively infrequently in each individual poem.

In my case, 17% of words in top 100 make their way into any one poem, whereas a once-again-considerable 43% of words in each poem are never repeated in another poem. To put it another way, my average poem is 72 words long, with 12 words in top 100 and 31 words that are never repeated in any other poem in either collection.

Interestingly, my individual top twenty-five lists isn’t an exact match of the top twenty-five for the other poems I analysed. For example, the number-one word across more than 3,000 high-quality Poetry magazine poems, “time”, is nowhere in my own top twenty-five. I suspect, however, that if I were to analyse poems on a poet-by-poet basis from these 3,000, the individual preoccupations and concerns would start to tease out, and many poets in Poetry would stray far from the norm as well.

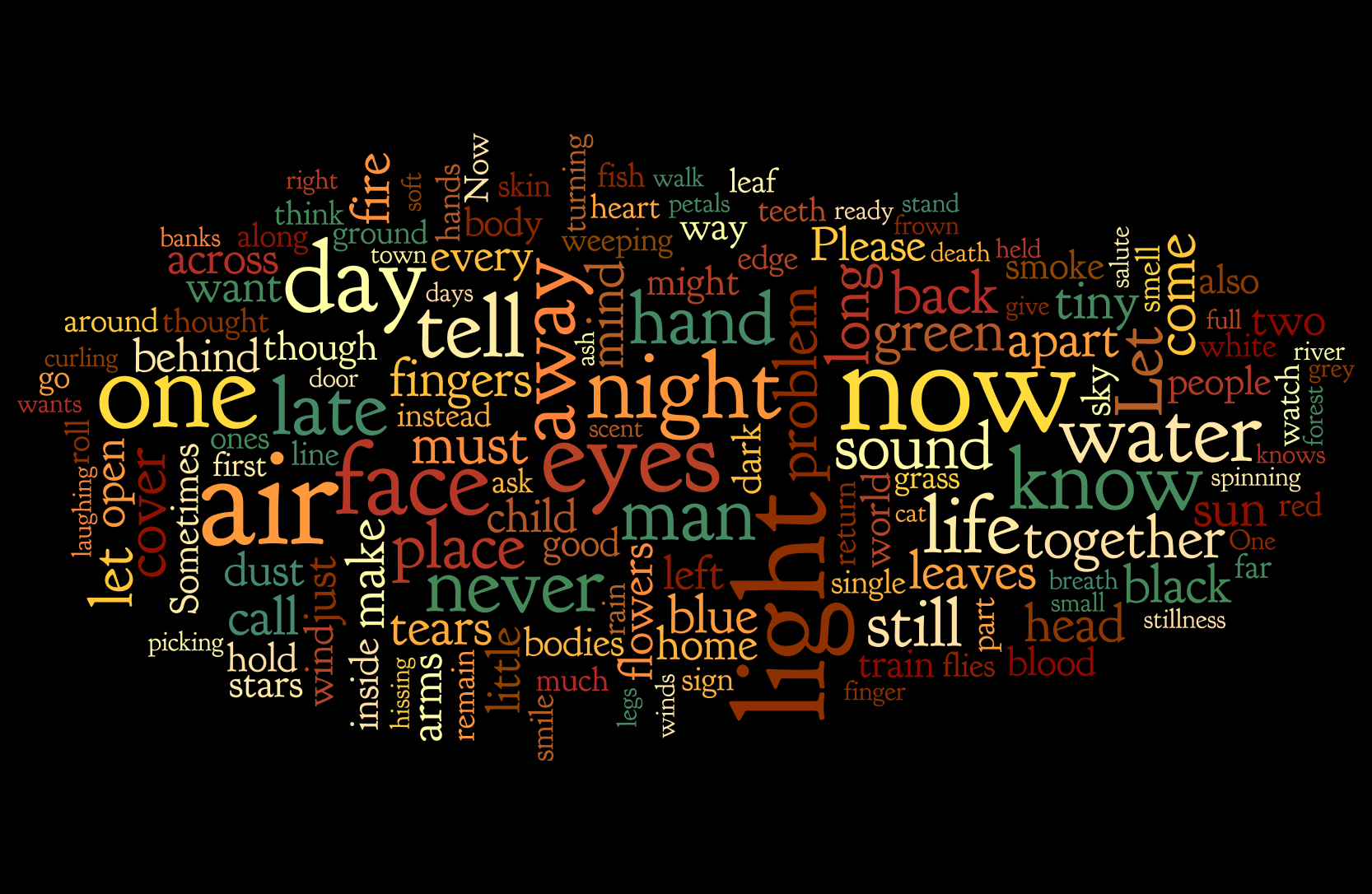

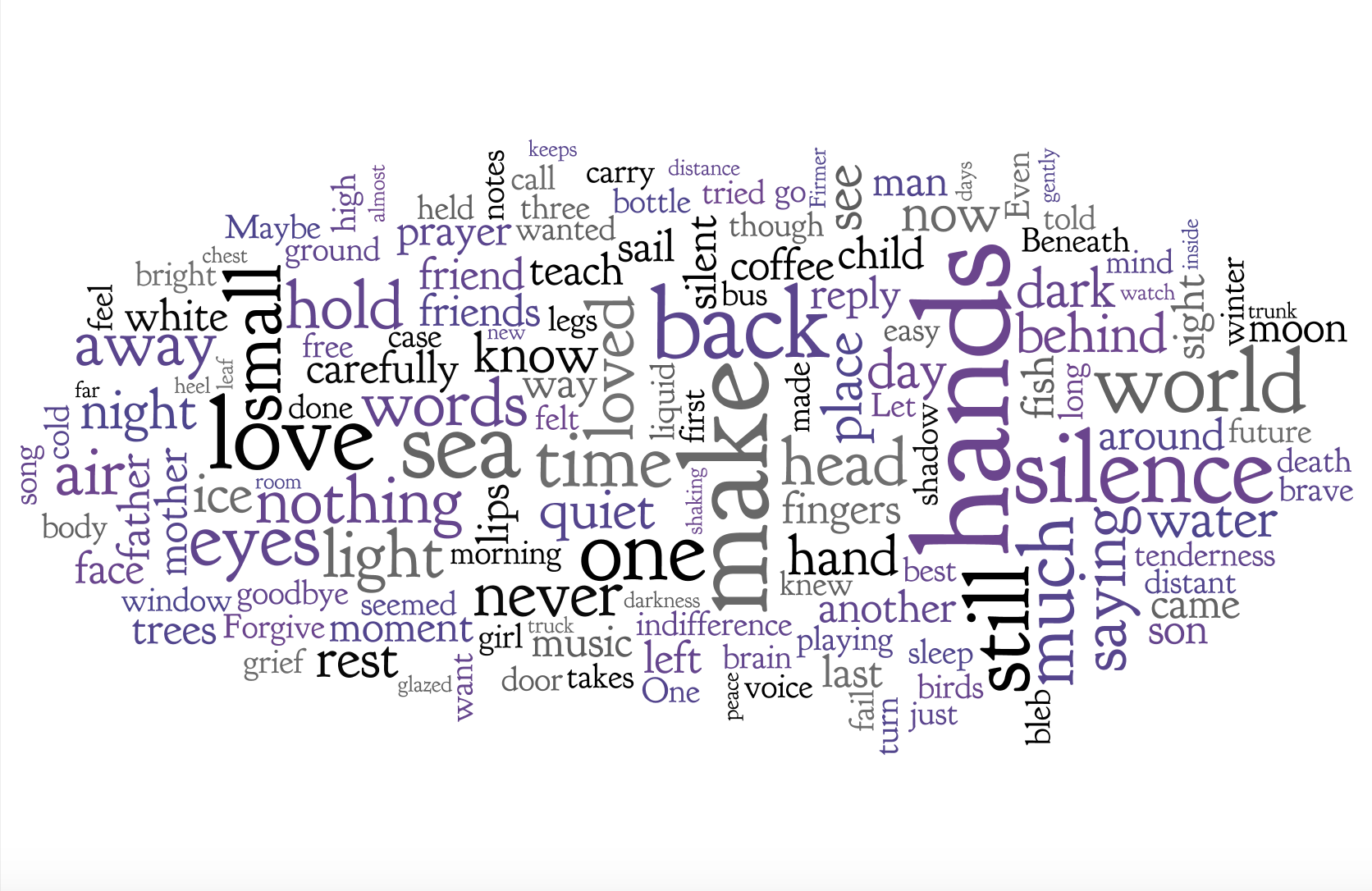

Furthermore, the specific concerns of my two books are very different from one another, as illustrated in the following word clouds:

The Knowledge

The Silence Teacher

So, individually, we’re all very different, from poet to poet and book to book, each with our own unique preoccupations. Yet collectively, when pooled, these preoccupations seem to converge on specific words.

What fascinates me about this is that purely analytical methods can reveal aspects of poetry that we readers and writers consciously miss. Computers counting words are not reading for meaning. They are able to highlight the similarities where a human reader sees only the differences.

Could it be that such non-human methods can therefore give insights into decidedly human phenomena, such as the individual and collective subconscious?

It would be interesting to analyse a significantly larger base of poetry texts, to see if they continue to converge on certain words.

For now, one thing is clear–these “Apollonian” words (as Dave Bonta so rightly identified them to be) make a frequent occurrence in all kinds of poetry, including fresh and lively contemporary poems.

Perhaps we poets have always been chasing after some element of the sublime (the top one hundred), but succeed in doing so in the postmodern age only to the extent that we can reinvent these timeless themes (aided, in part, by the non-repeating words). Emerson tells us that poetry, “must be as new as foam, and as old as the rock.” Perhaps the right mix of foam-words and rock-words is part of that endeavour.

Humans write poems for other humans, not for machines. Yet the mechanical analysis of text, correctly interpreted and contextualised, may indeed help us to see old words with new eyes.