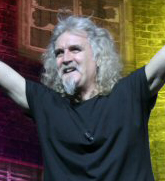

I had the pleasure of seeing Billy Connolly perform stand-up live in Los Angeles last night. Throughout the show, I kept noticing how he would continually branch from anecdote to anecdote, snaring our attention with unresolved themes, then finally resolving them (for the most part) to hilarious effect. More and more it occurs to me that in many ways poetry and comedy are very similar. Frustration itself has been a theme in poetry, especially love poetry, since Petrarch (and no doubt before). Yet poetry itself, by its very nature, is pleasurably frustrating in much the same manner as comedy.

I had the pleasure of seeing Billy Connolly perform stand-up live in Los Angeles last night. Throughout the show, I kept noticing how he would continually branch from anecdote to anecdote, snaring our attention with unresolved themes, then finally resolving them (for the most part) to hilarious effect. More and more it occurs to me that in many ways poetry and comedy are very similar. Frustration itself has been a theme in poetry, especially love poetry, since Petrarch (and no doubt before). Yet poetry itself, by its very nature, is pleasurably frustrating in much the same manner as comedy.

Flarf, for example, is funny in part because the same kinds of leaps we make in poetry are exaggerated to a ridiculous extent. There are numerous other structural and tactical parallels–the rule of threes, for example, being an easy way to set up a pattern and therefore expectation, only to simultaneously frustrate that expectation and offer a compensation that turns out to be humorous. It works as well in “a man walks into a bar…” jokes as it does in three-part lists in poems, and even the haiku form typically takes the opportunity in the third line to make some unique turn of mind. In comedy and poetry there is a kind of constant setup and slant delivery.

Furthermore, just as comedy has evolved from the vaudeville approach of getting up on stage and telling highly structured jokes with punch-lines to the much more elaborate and free-form modes of stand-up comedy today, so too has poetry evolved from proscribed forms into free verse. Yet this three-part experience: expectation, frustration and compensation–continues to exist in most modern poetic devices as well. It simply operates more subtly than “a man walked into a bar…” or rhyming couplets. Yet in poetry we do create, frustrate and compensate for our reader’s expectations constantly.

The difference between poetry and comedy lies partly in range and scope. Comedy typically only has one goal: laughter. Yet poetry can elicit a broad range of reactions. Furthermore, the scope of comedy is usually necessarily stretched. Exaggeration, the unexpected and the outlandish are endemic to comedy, whereas poetry that does the same often actually ends up comedic. So, the narrower scope–the less outlandish leaps in poetry–lend more range of expression.

That said, certain schools of contemporary poetics continue to push our tolerance for the distance between thoughts, the degree of cohesion–satisfaction of expectation–that we require of a poem. In the end, we still tell jokes and write formal verse. The age-old tricks still work. But this meta-trick, as it were, of pleasurably frustrating the mind, is an enduring characteristic of both poems and stand-up routines–so enduring, in fact, as to quite possibly be defining. What is poetry? Not quite getting what you want, and thereby getting something better, what Stephen Booth might call “understanding of something that remains something we do not understand.” How’s that for slant?